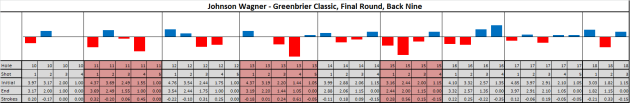

If we ever needed a lesson that golf is inherently random and statistics can only do so much to predict what will happen, Sunday’s final round at the Greenbrier certainly provided it. Johnson Wagner entered the final round leading Jimmy Walker by two strokes, with Jonas Blixt sitting three back. By the time Wagner was teeing off on #10 to start the back nine, Walker had not managed to close the gap at all, while Blixt had birdied #9 and #10 to get within a single stroke. From there, Blixt used several fantastic approach shots to set-up birdies, while Wagner made three crucial bogeys to fall out of the lead – handing Blixt his second PGA victory in less than a year. My analysis of the back nine will attempt to quantify strokes gained and lost on the field by each shot Wagner and Blixt made on the back nine, similar to my look at the Travelers.

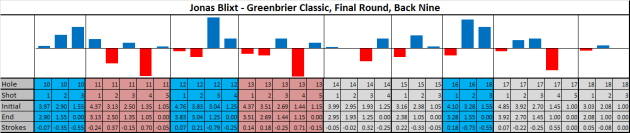

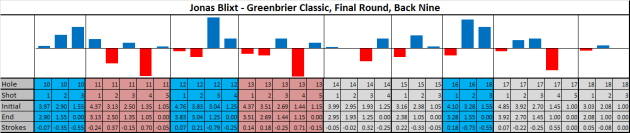

What was remarkable random about the back-nine was what shots Blixt hit to set-up birdies. Blixt is fairly categorized a player very reliant on his putting for success (he was 2nd in 2012 and 47th this season). He does not hit his approach shots well, sitting nearly at the bottom in GIR, even when we account for his below average performance on tee shots. However on Sunday, Blixt’s two best shots were his approaches on #12 and #16 that set-up birdies – both worth around 3/4ths of a stroke. On the flipside, his normally sterling putting failed him on #11, #13, and #17 setting up two bogeys and depriving him of what would’ve been a decisive birdie.

On the par 5 #12, Blixt sat 108 yards from the hole after his lay-up. From there the average player hits to around 20 feet. Instead, Blixt hit a beauty to five feet, setting up a birdie that tied him with Wagner at -13. Later at the par 4 #16, Blixt was 173 yards in the fairway, a location from which the average pro hits to around 30 feet. Blixt hit an iron to nine feet, producing a make-able birdie putt that he drained to draw ahead of Wagner at -13. His approach here was his 2nd best of the day, behind the approach on #12, and his subsequent putt was his 3rd best shot.

However, along with those great approaches came three awfully poor putts which resulted in a par and two bogeys. On the long par 4 #11, Blixt missed the green, but chipped to 6 feet. PGA players make 2/3rds of those putts; Blixt not only missed but ran it three feet past, leaving a miss-able putt for bogey that he made. He hit another equally poor putt on the long par 4 #13. After laying-up, Blixt hit to 7 feet, but blew his par putt four feet past the hole. He would make the four footer for bogey. Again on the par 5 #17, Blixt was standing over a 7 footer that would’ve put him three clear of Wagner. Seven footers are 55% putts normally, so Blixt’s miss cost him over half of stroke, but at least he didn’t blow it several feet past the hole.

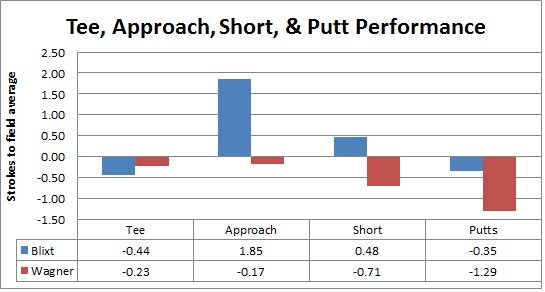

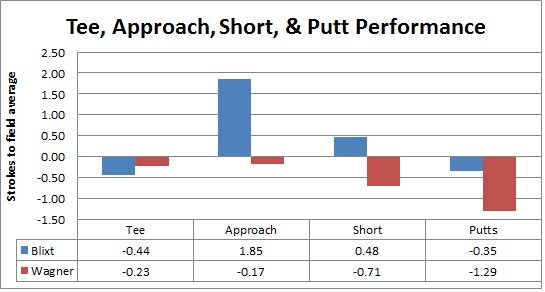

In total, Blixt’s back nine shots were worth: -0.44 strokes (tee shots), +1.85 strokes (approach shots), +0.48 strokes (short game), and -0.35 strokes (putts).

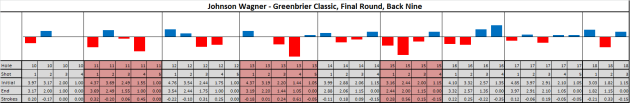

Johnson Wagner’s back nine was, succinctly, a disaster. He began it with a two stroke lead over Blixt that was quickly shortened to one stroke after Blixt’s birdie ahead of him on #10. At this point, no one else was any better than -11, while Wagner sat at -14. From there, Wagner bogeyed three of the next five holes and watched Blixt draw two strokes ahead of him for the win. For a guy who has been a steadily good putter (29th, 39th, and 41st in Strokes Gained in 2011-13), the flat stick failed him on Sunday. Two of his three worst shots were missed par putts inside 10 feet (on #11 and #13).

It was #15 that really sunk him though. He started #15 even with Blixt at -12. As we saw earlier, Blixt would go onto birdie #16, but Wagner would not have been in terrible position if he had parred #15 and moved on, as 16-18 aren’t difficult holes. His tee shot on the par 3 #15 was poor, ending up in the rough 14 yards from the pin. From there, PGA players bogey about half the time. Wagner blew his next shot 33 feet past the pin, leaving him a nearly guaranteed bogey. Within 15 minutes between Wagner’s bogey on #15 and Blixt’s birdie on #16, the tournament was all but over.

For the back-nine, Wagner finished -0.23 strokes (tee shots), -0.17 strokes (approach shots), -0.71 strokes (short game), and -1.29 strokes (putts), a thoroughly miserable performance for a guy who is a PGA Tour player because of his ability to putt.

Recent Comments