I have written a lot on the consistency of performance and using past performance to predict future performance. Once you have the data, those studies are straightforward to conduct and produce intuitive results. I’ve neglected much discussion of the mental side of the game because, on the whole, there isn’t any data out there that directly measures whether a player is confident, nervous, distracted, overwhelmed, able to cope with pressure, etc. I’ve just read two papers – Confidence Enhanced Performance by Rosenqvist & Skans and The Impact of Pressure on Performance by Hickman & Metz – that attempt to measure the psychological impacts on performance inherent in golf using performance data.

Confidence Enhanced Performance:

Rosenqvist & Skans use European Tour data from the past decade to measure the impact of confidence on performance. Because of the existence of the cut in most tournaments and the natural division of the field into successes and failures by the cut, it’s possible to look at how making or missing the cut affects performance in the subsequent tournament. Players who make or miss the cut are separated by very small differences in performance (as little as a single stroke for those directly on either side of the cut line) and are also nearly identical in terms of long-term talent. That means we should expect their performances to be similar in subsequent weeks – assuming that there isn’t any impact from prior weeks.

What Rosenqvist & Skans find is that there is a difference in performance between those who barely made the cut and those who barely missed the cut (they create these groups using players within six strokes of the cut in either direction, though they also compared smaller ranges). Players who just made the cut in the treatment tournament are ~3% more likely to make it in the outcome tournament. Players who make the cut also play ~0.125 strokes better per round in the first two rounds of the following tournament. The authors explain this outcome as a product of enhanced or diminished confidence effecting the players’s performance.

I’ve found similar impacts on performance in my own work. Players who exceed their normal or expected performance one week retain a small portion of that over-performance the following week; that is, they continue to perform slightly better the following week. The same is true for those who play worse than expected. It’s very difficult to say precisely why this occurs.

The authors say it’s because the player in question is more or less confident than normal. They designed their study to directly compare players with similar performance who were clearly separated into successes and failures. However, the difference in strokes between making and missing the cut is still large – even comparing only those players on either side of the cut line. In their study, the smallest range they examined was those players within four strokes to either side of the cut line. There is still a substantial difference in performance between the two groups; the missed cut group on average played one stroke per round worse than the cut line and the made cut group on average played one stroke per round better than the cut line. That shows a two stroke difference between the two groups of players. The authors showed that both groups were comprised of fairly similar players, so the made cut group slightly overachieved by roughly one stroke per round and the missed cut group slightly underachieved by roughly one stroke per round.

So the authors were not comparing players who were separated only into a successful and an unsuccessful group. They were comparing players who were successful/had overachieved versus a group who were unsuccessful/had underachieved. It’s impossible, with this data, to state that the observed differences in making or missing the next cut can be explained by confidence versus other factors. The slightly higher probability of making the cut in subsequent tournaments can be just as easily explained by saying the player’s swing was slightly better than normal or that his mind/body were in better physical condition. Teasing apart the impact of psychological vs. physical is difficult – perhaps impossible without administering a psychological evaluation and analyzing Trackman launch monitor data.

The authors’s finding of a small carry-over in performance is the important discovery, though. They show that players who perform well the previous week perform slightly better the following week than those who did not perform well the previous week – by around 0.125 strokes per round. However, this impact is extremely small and is surely overstated by those writing about and discussing golf. Good play the previous week only barely increases the probability that you will play well the following week. This reinforces the importance of looking at long-term performance when attempting to predict future performance.

The Impact of Pressure on Performance:

Hickman & Metz use Shot Link data to examine the probability of making a putt on the last hole of a tournament, considering the amount of money riding on the putt, the distance of the putt, the experience of the player, the amount of money the player won in the previous season, and the putting performance of the player so far in the tournament. They find that for every ~$30,000 that is riding on a putt (ie, if someone makes they win $100,000 and if they miss they win $70,000) the probability of making the putt drops by 1% all else being equal. They also find that this most impacts short putts of between 3 to 12 feet.

I don’t have much to say about this study except that I wish the authors had included a better control for putting ability. They controlled for ability using Total Putts Gained (basically Strokes Gained Putting throughout the tournament). Unfortunately, putting performance in small samples like one tournament is essentially noise. If you know how well a player putts in general, how well they are putting in a tournament isn’t predictive at all. In their study you’ll see that TPG is a significant factor in predicting the probability of making a putt, but if you look at the coefficients you can see that for every Total Putt Gained in the tournament (or for every 0.25 TPG in each round) the probability of making a putt increases by 0.9%. Over 18 holes this would translate to 0.16 putts gained. So players who putt well, in general, will tend to putt well in a tournament, so they’ll tend to make slightly more putts on the 18th hole. I don’t think this effects their results, but I do wish they’d controlled for ability in a better way. It’s possible that good putters block out the pressure better, or that bad putters are less affected by pressure.

Edit: It’s also unclear whether they take putts gained on the final hole out of their TPG measure.

However, the effect they’ve found is significant in terms of examining the impact of pressure. It indicates that for putts with very large differences in prize money (for example the Bubba Watson example they quoted on page 9 where $300,000 was on the line) the difference in probability of making the putt compared to a non-pressure situation could be up to 10%.

The Impact of Tournament Position on Performance:

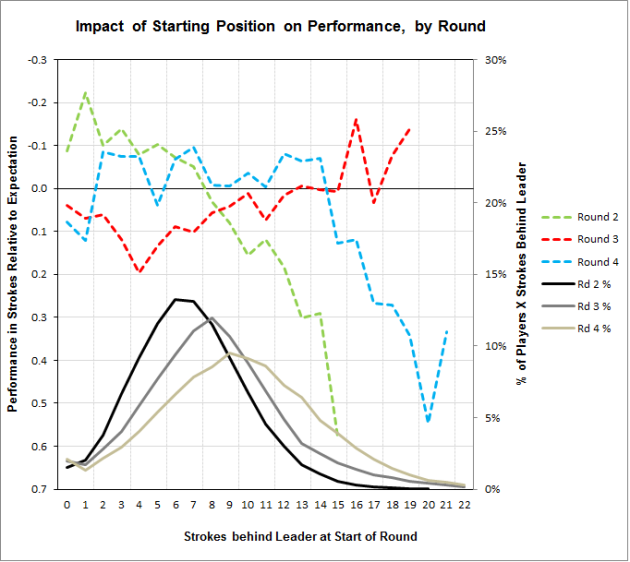

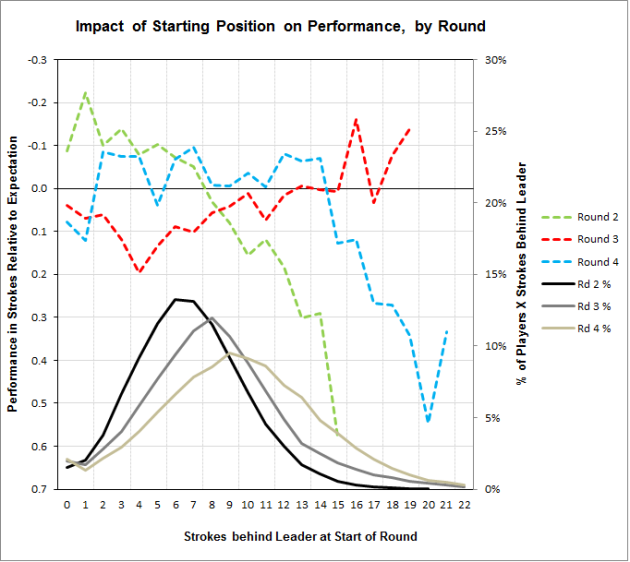

I’ve dug into my database of results for the last half decade and examined the impact on performance of starting position in terms of strokes behind the leader. I’ve found two interesting results: 1. players who begin the second and fourth rounds a large number of strokes behind the leader perform worse than expected (I have compared all performance to my expected z-score performance) and 2. players who begin the fourth round in the lead or one stroke back perform worse than those who begin the round near the leader, but further back. For #1, it’s possible that these players are out-of-form (whether because of injury, swing, fatigue, etc.) or that they’re “giving-up” – focusing less because there’s less on the line for them. For #2, I suggest that players near the lead “choke” or play slightly worse than normal because of pressure.

It’s the nature of a golf tournament that after the second round a cut is taken that eliminates the worse half of the field. After the fourth round, prize money is awarded based on finish – with those at the top earning as much as 17% of the purse and most of those near the bottom earning prizes of around 0.5-1% of the purse. In other words, players who begin the second round far behind the leaders normally will not be able to make the cut, while those who begin the fourth round far behind the leaders are normally locked into a very small prize. This means that players who are near the bottom beginning the second and fourth rounds aren’t playing for much; the first group is likely to miss the cut and earn nothing while the second group is largely locked into a small prize. I’ve found the negative impact on performance to be as much as a quarter to half a stroke for those near the bottom of a leaderboard (the green and blue lines on the below graph). It’s impossible, with this data, to attribute this effect to “giving-up” or to physical factors – out-of-form swing, injury, fatigue, etc.

Similarly, if you focus on the fourth round results in blue, you can see that players in positions zero and one strokes behind the leader performed approximately 0.1 strokes worse than expected while those in positions two to seven strokes behind the leader performed approximately 0.06 strokes better than expected. All of these players had a reason to remain fully engaged mentally with the tournament. Those finishing in the positions they started the round in stand to earn the large prizes. This shows that players who begin the round in or near the lead typically play slightly worse than would be expected by their prior performance, and more importantly that the same is not true for players who begin the round in close positions, but not in or right behind the leader. This reinforces the idea that pressure exerts a negative effect on those in the lead.

I also should address the red line for the third round. Players in the third round begin in opposite order of performance so far, meaning those furthest back of the leader tee of early, while those closest to the leader tee off late. PGA Tour courses play more difficult, in general, in the afternoon than the morning. Steven Rachesky found a difference of roughly 0.15 strokes between early and late tee-times – similar to the results I’ve observed from my data. That is the major reason why the data for the third round looks drastically different.

Pingback: 2015 Humana Challenge Preview | Golf Analytics